Leonardo da Vinci on painting stands out as one of history’s most transformative approaches to visual art. He fundamentally changed how artists saw their craft.

The Renaissance master didn’t just make beautiful pictures. He transformed painting into a scientific discipline, combining precise observation, mathematical principles, and innovative techniques that had not been attempted before.

Leonardo revolutionized art by treating painting as both a science and an art form. He employed detailed anatomical studies, a mathematical perspective, and experimental techniques like sfumato to create realism and depth that no one else managed at the time.

His methods went far beyond the usual painting approaches of his era. Leonardo brought in engineering ideas and scientific observation to get effects that felt almost magical.

From his anatomical sketches, which revealed the inner workings of the human body, to his use of light and shadow, Leonardo set new standards that artists still study. His influence stretched from his own masterpieces to teaching methods that shaped generations of artists.

He helped transform art from simple decoration into a blend of creativity and scientific precision. That’s a legacy that really changed the game.

The Scientific Odyssey of Painting

Leonardo da Vinci’s approach to painting changed art by systematically applying scientific principles. He established painting as a science grounded in mathematics, optics, and close observation of the natural world.

His approach merged art and science, utilizing geometric perspective, anatomical accuracy, and a careful study of how the world works. He wasn’t just painting; he was conducting an investigation.

Painting as a Science & Imitation of Nature

Leonardo raised painting above mere craft, treating it as a universal art rooted in scientific principles. He saw painting as the ultimate imitation of nature, demanding a deep understanding of natural phenomena, rather than merely copying what one sees.

He insisted that painters study light, atmosphere, and living forms. Leonardo believed that effective painting required an understanding of anatomy, botany, geology, and physics.

Painters, he said, had to grasp causes and effects in painting. Every shadow, reflection, and color shift needed a scientific reason behind it.

This way of thinking set Leonardo apart from artists who primarily relied on tradition or gut feeling. He wanted art backed by knowledge.

Leonardo’s scientific approach to painting created systematic methods for achieving verisimilitude through careful observation and analysis.

Method and Inquiry: Experiment and Observation

Leonardo’s philosophy centered on method and inquiry—direct experimentation and observation, rather than relying solely on old books or established habits. He wanted to see for himself.

He kept detailed notes and filled sketchbooks with experiments on light, color, and surface. Precise drawings and written notes accompanied every observation.

He pushed for studying nature as the key to becoming a real artist. Leonardo believed that drawing was the foundation for all painting and that artists should work from life, rather than just from imagination.

His step-by-step method included mirror observation and even memory training exercises. In his studio, students moved from basic drawing to more complex painting in an orderly, hands-on way.

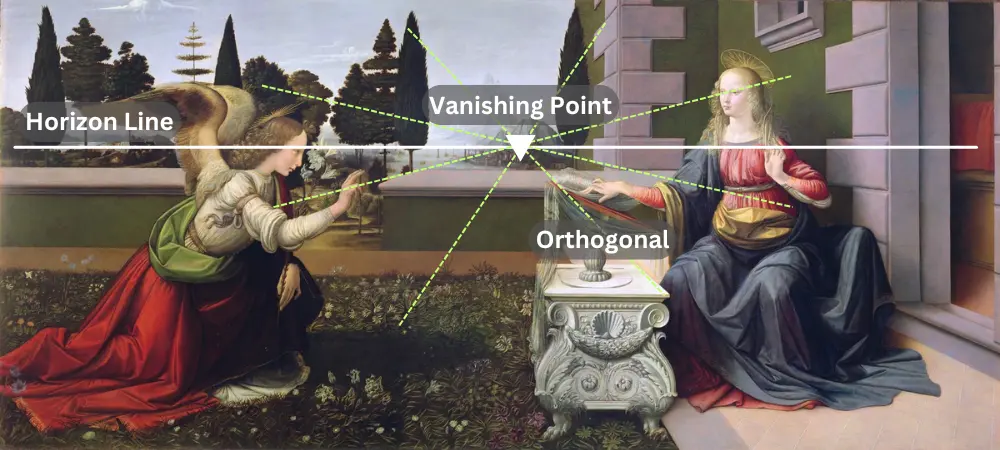

Geometry in Art: Linear Perspective, Vanishing Point & Orthogonals

Leonardo mastered the math behind linear perspective. He established clear rules for vanishing points and orthogonals to create convincing spatial depth and proportion.

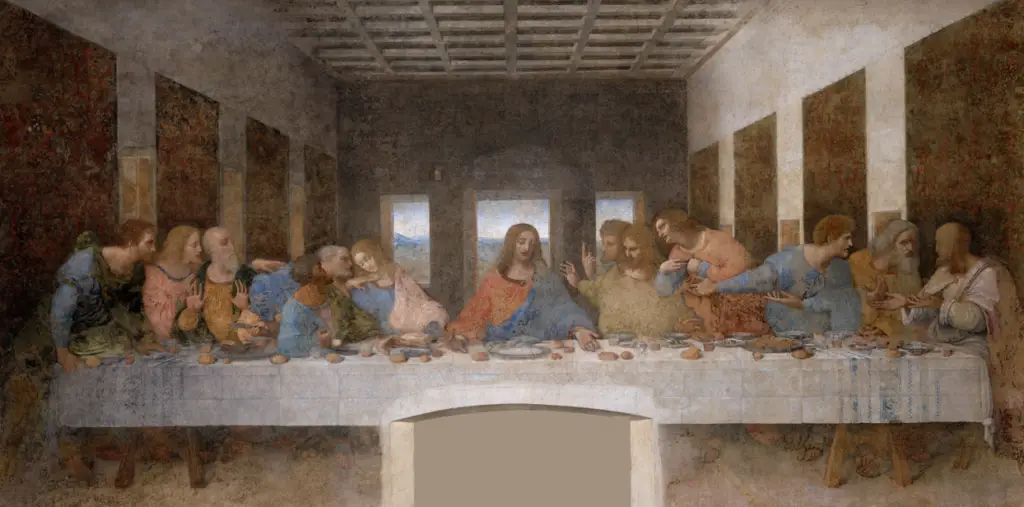

Leonardo’s use of perspective and proportion is evident in works like The Last Supper. He calculated lines converging toward focal points to guide the viewer’s eye.

He also brought in aerial perspective and atmospheric perspective. Leonardo figured out how distance makes things appear smaller and colors shift toward blue as objects recede.

He applied mathematics to every part of his compositions, from arranging figures to designing buildings and landscapes. It was all connected.

Physiology & Optics of Vision: Anatomy in Paint

Leonardo’s anatomical studies changed figure painting by revealing musculature and motion in detail. Cutting open cadavers gave him knowledge of human proportion and physiognomy that nobody else had.

His research into optics and vision shaped his painting techniques. Leonardo wanted to know how the eye perceives form, color, and distance, so he could paint what people actually see.

He developed a sophisticated sense of human proportion and studied the differences between child and adult bodies. He analyzed how limbs moved in different poses.

Leonardo also cataloged gestures and expressions. He studied how faces move and what those motions mean emotionally. It’s almost like he was part scientist, part psychologist.

Codex Urbinas & Trattato della Pittura: Evidence and Analysis in Scientific Discourse

The Codex Urbinas preserves Leonardo’s painting theories, compiled by Francesco Melzi. This collection demonstrates his commitment to scientific discourse and the application of evidence and analysis in art.

The Trattato della pittura set out clear rules for young painters. Leonardo’s treatise covered everything from basic drawing to complex composition.

He argued for the supremacy of sight and claimed painting was the superior art. Leonardo compared painting to sculpture, poetry, and music, making his case for why painting was the most important of the arts.

The treatise also included practical advice, such as oil painting techniques, glazing, and underpainting methods—his systematic approach to color mixing and surface preparation set standards that studios still use.

Mastering Depth and Light in the Canvas Cosmos

Leonardo da Vinci on painting changed Renaissance art with new ways to show atmospheric perspective and chiaroscuro. He sculpted forms with light and shadow, and his study of optics and anatomy set new standards for realism.

Atmospheric & Aerial Perspective: Diminution with Distance

Leonardo figured out how aerial perspective makes distant objects appear lighter, bluer, and less defined due to the effects of the atmosphere. He didn’t just guess—he observed and tested.

This atmospheric perspective involved shifting colors toward cooler tones as objects receded in space. Mountains in his paintings fade into haze and lose their punch the farther away they get.

He applied diminution with distance carefully. Objects farther away shrink in size, contrast, and detail, following mathematical rules.

Leonardo’s mastery of atmospheric perspective gave his paintings a real sense of spatial depth. Just look at the Mona Lisa—the background mountains show off this trick perfectly.

Chiaroscuro & Sfumato: Light, Shade, and Smoke

Leonardo used chiaroscuro—strong contrasts between light and dark—to shape forms in three dimensions. He treated painting like a science, really thinking about how light acts on surfaces.

His sfumato method created smoky contours with subtle blending, characterized by soft transitions and gentle shifts, rather than harsh lines.

Leonardo’s chiaroscuro mixed directional lighting with graduated transitions between light and shadow. This gave his work both drama and a lifelike feel.

Soft edges replaced the hard outlines used by earlier artists. His tonal unity made the figures seem to rise out of the darkness—almost as if they were breathing.

Modeling Form with Tone: Graduated Transitions & Veils

Leonardo invented complex glazing techniques with thin, see-through layers of paint. These veils and glazes built up color and created glowing effects.

He understood that modeling form with tone meant knowing how light wraps around shapes and picks out textures. He studied how illumination curved around spheres and played on sharp edges.

His step-by-step method started with careful underpainting and built up layers of glaze. Each layer tweaked the colors underneath but kept them luminous.

Leonardo handled edges differently depending on the form and the light. Graduated transitions made things look round, but he never lost the structure.

Landscape as Character: Clouds, Dust-Filled Air & Geology

Leonardo didn’t treat landscapes as throwaway backgrounds. He studied rocks and geology closely, making them part of the story.

He paid special attention to clouds and smoke as ways to show off atmospheric effects. You can see his interest in how fluids and light interact.

Dust-filled air and mist provided him with more opportunities to utilize atmospheric perspective. These effects linked the foreground and background through consistent lighting.

His geological studies led to the creation of realistic rocks and mountains. Botany and trees followed observed branching patterns that matched how things really grow.

Human Proportion and Expression: Canon, Physiognomy & Gestures

Leonardo’s canon of proportions set up mathematical relationships between different body parts. Through anatomical study and dissection, he brought an accuracy to musculature and motion that few had seen before.

Physiognomy studies enable him to see how facial features convey character and emotion. He catalogued gestures and expressions to build believable, lively narrative scenes.

He paid close attention to the movement of members, capturing figures in dynamic, ongoing action. By comparing child and adult proportions, he showed a systematic approach to human variety.

Drapery folds adhered to the principles of physics, contributing to the flow of each composition. Studying fabric meant knowing both how materials behave and what lies beneath them.

From Sketchbook to Sistine: Leonardo’s Teaching Legacy

Leonardo da Vinci changed art education with systematic drawing methods, detailed note-taking, and theoretical writings that raised painting to a science. He blended direct observation of nature with math, building a framework that shaped generations of artists through his treatise.

Drawing as Foundation: Study from Nature & Note‑Taking

Leonardo made drawing the foundation of artistic practice. He said studying from nature mattered more than copying old traditions.

His method pushed students to observe life directly. Artists drew plants, animals, and people in real settings, not just from other artworks.

In his sketchbooks, Leonardo took detailed notes alongside his drawings. Throughout his career, he filled them with more than 13,000 sketches and written observations, seamlessly blending art and science at every turn.

Mirror observation was a favorite teaching trick. Students used mirrors to see their work with fresh eyes, catching mistakes and fixing composition problems.

Studio Practice & Step‑by‑Step Method: Rules, Precepts, Pedagogy

Leonardo set up systematic studio practice methods to train young painters. His step-by-step method broke big artistic problems into smaller, doable steps.

The training sequence followed clear rules and precepts:

- Start by copying master drawings

- Move on to drawing from plaster casts

- Then draw from live models

- Study anatomy through dissection

- Practice linear perspective and vanishing point construction

He wanted students to understand, not just copy. They learned the causes and effects in painting through experiment and observation, setting his teaching apart from older workshop traditions.

Memory training mattered too. Students practiced recalling visual details without looking back, helping them create from imagination while staying accurate.

Paragone: Painting vs Sculpture, Poetry & Music

Leonardo championed painting’s supremacy of sight in the paragone debate. He called painting the universal art, outshining other creative fields.

He said painting beat sculpture because it could show:

- Atmospheric perspective and deep space

- Chiaroscuro and sfumato effects

- Multiple viewpoints at once

- Transparent and shiny surfaces

He argued that painting speaks instantly to the eye, while poetry takes time to read. The eye, as the noblest sense, could grasp a whole story in a single glance.

Music, he said, was beautiful but fleeting; painting, on the other hand, gave lasting visual pleasure. Leonardo’s theory elevated painting to the same level as math and natural philosophy.

Trattato’s Impact: Abridged 1651 Edition to Modern Translations (1817)

Francesco Melzi compiled the Trattato della pittura from Leonardo’s scattered notes around 1540. The Codex Urbinas brought thousands of thoughts together in organized chapters.

The 1651 abridged edition disseminated Leonardo’s theories more widely across Europe, influencing Baroque and Neoclassical artists in France, Italy, and Northern Europe.

Modern translations starting in 1817 revealed Leonardo’s complete teaching system. Scholars found he connected optics and vision with practical painting skills.

Today, anthologies and translations continue to expand access to his teachings. Digital platforms offer his notebooks and theoretical writings to anyone, anywhere.

A Universality Achieved: Art, Science, and the Renaissance Ideal

Leonardo achieved a remarkable universality in painting by fusing artistic skill with scientific method and inquiry. He demonstrated how the mathematics of art can enhance creativity.

Through dissection, he learned anatomy and human proportion inside out. This made his figures move and gesture in believable ways.

Botany and branching rules shaped his landscapes. His hydrology and water studies made flowing forms and atmospheric effects more convincing.

Leonardo’s approach made art education an intellectual pursuit, not just a craft. He proved that to excel, artists had to understand nature’s laws by observing and analyzing the world.

Final Thoughts

Leonardo da Vinci on painting shook up the art world with techniques that still shape artists today. His mastery of sfumato, chiaroscuro, and anatomical detail set new standards for what art could be.

Key Takeaways: Da Vinci’s painting breakthroughs combined scientific observation and artistic expression, resulting in Renaissance masterpieces. His sfumato and perspective methods still echo in art schools everywhere.

He treated painting as more than an aesthetic pursuit, almost like a scientific experiment. He studied light, shadow, and anatomy with unmatched curiosity.

His impact on art endures, inspiring generations of painters and sculptors. The Mona Lisa and The Last Supper still spark debate and study today.

Modern artists still look to his methods:

- Sfumato for soft transitions

- Mathematical perspective

- Anatomical accuracy

- Scientific observation in art

His notebooks show a mind that never split art from science. That interdisciplinary spark changed how artists saw their craft—and themselves.

Leonardo da Vinci’s legacy in painting is far greater than his limited number of finished works. He proved that true innovation in art can ripple through centuries and keep creativity alive.

Frequently Asked Questions

Leonardo da Vinci’s painting theories revolutionized how artists approached their work, blending science and technique in ways that remain influential. His belief in art as a science and his famous quotes continue to shape painters’ thinking, while debates about his works and their meaning demonstrate the enduring fascination with his legacy.

What did Leonardo da Vinci say about painting?

Leonardo called painting the highest form of knowledge and saw it as a science. He said painters needed to study math, anatomy, and nature to make art that’s true to life.

He wrote that painting captures reality better than poetry or music because it shows things directly to the eye. He told artists to observe shadows, light, and human expressions.

Leonardo’s new approach to painting insisted that artists understand their subject matter entirely. He believed anatomical knowledge was essential for drawing the human body correctly.

What did Leonardo da Vinci believe about art?

Leonardo thought art and science belonged together. He believed that artists should study the natural world like scientists to create paintings that feel authentic.

He saw painting as the top art form because it could show 3D space on a flat surface. In his view, that made painting better than sculpture or music.

His scientific approach to art involved close examinations of water, plants, and movement. He used these studies to make his paintings more lifelike.

What is Da Vinci’s most famous quote?

Leonardo’s best-known quote is “Learning never exhausts the mind.” He truly believed that constant study and observation were essential for both artists and scientists.

Another favorite is “Painting is poetry that is seen rather than felt, and poetry is painting that is felt rather than seen.” He clearly saw painting as the equal of other arts.

He also said, “The noblest pleasure is the joy of understanding,” demonstrating his appreciation for combining art with scientific thinking.

Who bought the $450 million painting?

The painting “Salvator Mundi” sold for $450.3 million at Christie’s in November 2017. The buyer’s identity remains officially unknown, although some reports suggest it was purchased through intermediaries.

Some sources claim it was for Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, but neither the auction house nor the buyer has confirmed that. The painting depicts Jesus holding a crystal orb, showcasing Leonardo’s skill with light and transparency.

What is the painting in the Da Vinci Code?

The painting at the heart of Dan Brown’s “The Da Vinci Code” is “The Last Supper.” The novel spins theories about secret messages and symbols in this masterpiece.

The Last Supper shows Jesus announcing his betrayal to his disciples during their final meal together. Leonardo painted it between 1495 and 1498 on the wall of a monastery in Milan.

The book also mentions the “Mona Lisa” and offers fictional interpretations of both works, but art historians don’t support these views.

What painting do they believe Leonardo did not paint?

“Salvator Mundi” gets the most debate among scholars about whether Leonardo actually painted it. Some experts argue he only worked on parts of it, letting his workshop finish the rest.

The painting underwent extensive restoration before its record-breaking sale. That makes it challenging to tell what’s original brushwork and what isn’t.

Several art historians are unsure whether there’s enough of Leonardo’s hand left to call it truly his. It’s a tricky call, honestly.

Other disputed works include “La Belle Ferronnière” and several versions of religious scenes associated with his workshop. Scholars continue to examine these paintings with modern technology, hoping to determine where Leonardo’s work ends and that of his students begins.

Leonardo Bianchi,

the creator of Leonardo da Vinci's Inventions.

Thank you for visiting

Leonardo Bianchi,

the creator of Leonardo da Vinci's Inventions.

Thank you for visiting