The da Vinci bridge has captured the imagination of engineers and history buffs for centuries. Leonardo’s ambitious 1502 design would have stretched 919 feet across the Golden Horn in Istanbul—about ten times longer than most bridges.

Recent MIT research shows that Leonardo’s 500-year-old bridge design would have actually worked if built with the materials and methods available in his day.

The MIT engineers built detailed models and found that his engineering concepts still stand up to scrutiny.

Leonardo’s rejected bridge idea later found new life in Norway. His self-supporting design is a masterclass in Renaissance innovation, and honestly, anyone can try building a working model themselves.

The da Vinci Bridge in Real Life: From Leonardo’s 1502 Sketch to Modern Reality

Leonardo’s 1502 bridge proposal for Sultan Bayezid II sat on the shelf for centuries. Modern engineers eventually proved it was totally doable.

His flattened arch design later inspired a Norwegian pedestrian bridge and got the stamp of approval from MIT researchers.

Leonardo’s Letter to Sultan Bayezid II and the Golden Horn Design Proposal

In 1502, Leonardo da Vinci sketched what could’ve been the world’s longest bridge, spanning 280 meters across Istanbul’s Golden Horn. He sent this bold plan to Sultan Bayezid II during diplomatic talks between Italy and the Ottomans.

Leonardo tackled the tricky Haliç inlet with a single-span solution—no supports in the water, just one big leap. His letter described a stone bridge connecting the old city to the north side.

He designed it so ships could pass beneath and impress the Ottoman capital. Leonardo clearly understood both engineering and politics.

The Flattened Arch Concept: Revolutionary Compression-Only Structure

Leonardo used a flattened parabolic arch, so the bridge handled all loads through compression. That meant no need for cables or other tension elements—perfect for the stonework of the 16th century.

The keystone shape made it a deck-arch bridge. Compared to old-school semicircular arches, his design was lower but still strong. The abutments pushed back against the outward forces from the arch.

Key structural features included:

- Single-span masonry idea

- All compression load paths

- Wind resistance built in

- Flexible shape for earthquakes

Engineering Ambitions: The 280-Meter Span and Site Challenges

The 280-meter span would’ve smashed records for the time. Leonardo sized it to fit the Golden Horn’s wide gap and busy waterways.

Soft soils and earthquakes made the site challenging. Leonardo’s flexible arch and careful foundation design mitigated these risks.

He left enough clearance for tall-masted ships. That detail shaped the bridge’s whole structure—he really thought it through.

Why the Original da Vinci Bridge in Real Life Was Never Built

The bridge was never built in Leonardo’s lifetime, mostly due to politics and money. The Ottomans liked the idea but never took action.

Building a 280-meter stone span back then would have cost a fortune. Quarrying, hauling, and skilled labor just weren’t in the budget.

Shifting political winds between Italy and the Ottomans helped sink the project.

MIT Proves da Vinci Bridge Design: The 3D-Printed Scale Model Validation

MIT engineers put da Vinci’s wild bridge idea to the test with 3D-printed models. They stuck to period-appropriate materials and techniques.

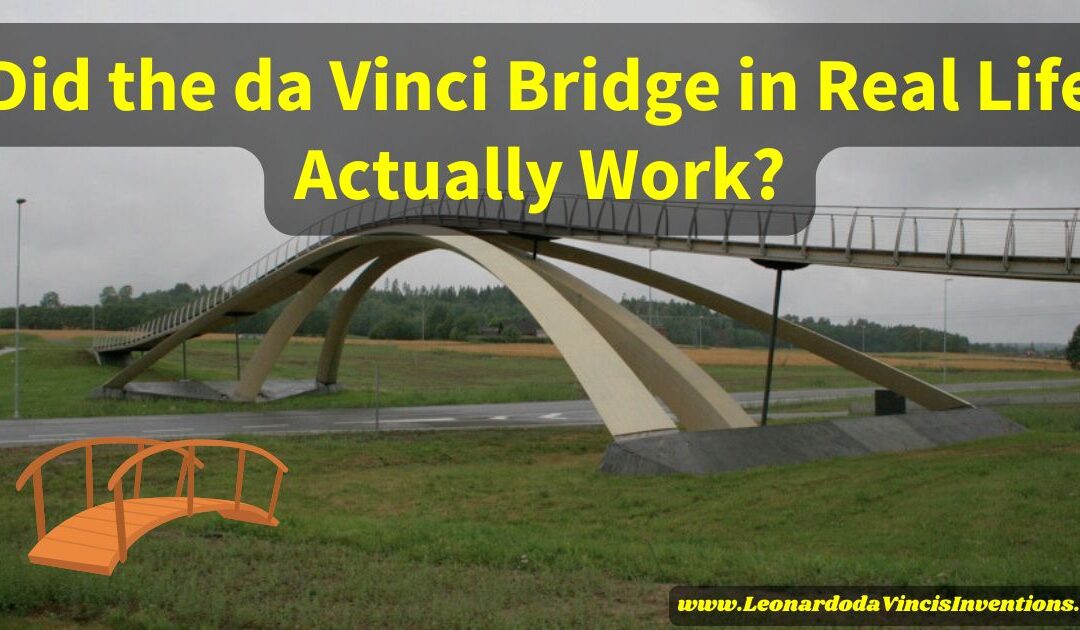

Norway’s da Vinci Bridge, a pedestrian overpass opened in 2001, borrows from the 1502 sketch but uses laminated wood and steel. You’ll find it in Ås, crossing the E18 highway.

The Vebjørn Sand Leonardo Bridge Project made the da Vinci bridge a reality in Norway, opting for glulam construction. Queen Sonja opened the bridge in 2001, finally bringing Leonardo’s vision to life.

The Norway Realization: da Vinci Bridge in Real Life as a National Landmark

Norwegian artist Vebjørn Sand and the Norwegian Public Roads Administration teamed up to make da Vinci’s bridge happen. In 2001, the Ås pedestrian bridge turned Leonardo’s 1502 idea into a real glulam structure.

Vebjørn Sand and the Leonardo Bridge Project Vision

In 1996, Vebjørn Sand stumbled across Leonardo’s bridge sketch and saw a chance to build it for real. He pitched the idea to the Norwegian Public Roads Administration—why not make the world’s first da Vinci bridge?

The Leonardo Bridge Project became both an art piece and an engineering challenge. Sand wanted a public art project to show Renaissance engineering with modern materials.

Norwegian officials liked the idea because they valued art in public spaces. Sometimes, the stars align.

The Ås, Norway Pedestrian Bridge: Bringing the da Vinci-Broen to Life

The da Vinci-Broen crosses the E18 highway in Ås, about 20 kilometers from Oslo. Construction started in 1997, and Queen Sonja officially opened it in 2001.

This pedestrian bridge is 109 meters long and has a 40-meter main span. It uses three parabolic arches—one in the middle for the walkway and two on the sides for stability.

The project cost around 13 million kroner. Locals went from calling it “Norway’s ugliest bridge” to praising its Renaissance-inspired elegance.

Modern Materials: Glulam da Vinci Bridge Construction

The Norwegian bridge swapped Leonardo’s stone for laminated wood, or glulam. Moelven Laminated Group, known for the 1994 Winter Olympics wooden roof, supplied the timber.

Steel adds extra strength but doesn’t mess with the look. Builders use cranes to put up big prefabricated sections.

Construction Materials:

- Glued laminated timber (glulam)

- Steel reinforcement

- Prefabricated timber sections

This approach showed that Leonardo’s compression-only structure also works with modern, sustainable materials.

Shorter Modern Realization vs. Original Span

Leonardo’s original plan called for a 240-meter span over the Haliç inlet. The Norwegian version shrunk it to a 40-meter span, just right for the E18 highway.

MIT researchers built a 3D-printed scale model and found Leonardo’s design would have worked at full scale, even with 16th-century stone.

The modern, smaller version proves that the old engineering still holds up when you adapt it.

Da Vinci Bridge in Real Life Norway: Iconic Design Brought to Life Centuries Later

The Norwegian bridge shows that Renaissance engineering isn’t just for history books. Leonardo’s flattened arch and compression tricks also work for modern foot traffic.

The design has drawn global attention—think New York Times, Wired, and others. It’s proof that old ideas can spark new, sustainable solutions.

The bridge is both a practical crossing and a work of art. Norway has a new landmark, and Leonardo finally gets his due.

Building Your Own Self-Supporting da Vinci Bridge: Educational Models and Activities

Making your self-supporting da Vinci bridge is a fun way to learn about Renaissance engineering. Projects range from popsicle-stick challenges to full-on museum exhibits—Leonardo’s ideas are surprisingly hands-on.

The Self-Supporting da Vinci Bridge Concept: No Fasteners Required

The self-supporting bridge relies on compression and tension between interlocked wood pieces. It does not use nails, screws, glue, or rope—just clever geometry.

Leonardo’s 1502–1503 Golden Horn proposal used this principle. The bridge holds itself up through careful placement and balance.

Modern models use the same compression-only setup. Students can make sturdy bridges from nothing but sticks. The keystone shape spreads the load across the whole span.

Popsicle-Stick Bridge Activity: Hands-On Learning for Students

Engineering activities for kids often involve building Da Vinci bridges with craft sticks and some physics. These projects include experimenting with stability and load paths.

Materials needed:

- Wooden craft sticks or popsicle sticks

- No adhesives or fasteners

- Flat building surface

Students learn by locking sticks together to make a stable bridge. The step-by-step process teaches geometry and basic engineering.

It usually takes a few tries to get it right. That trial and error is half the fun—and it really drives home how clever Leonardo’s design was.

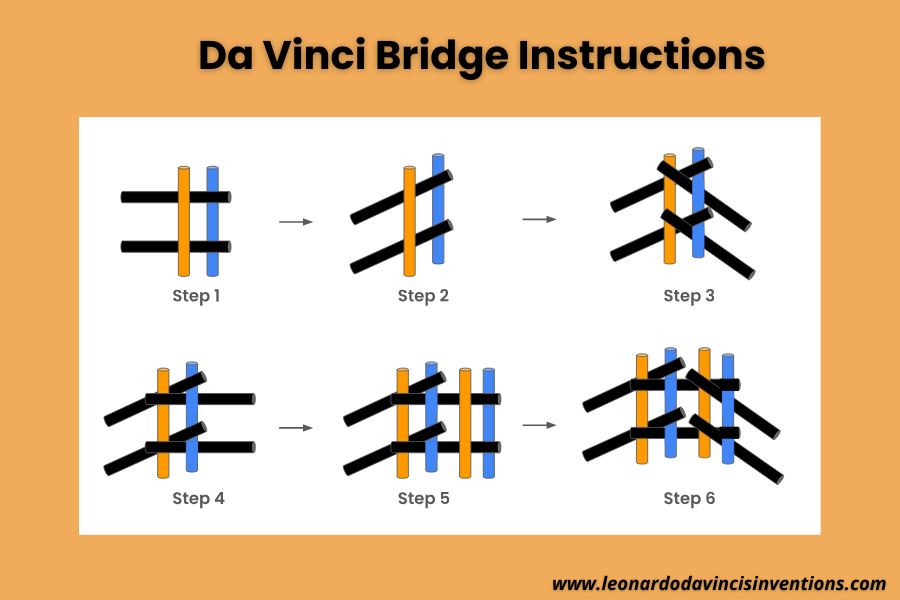

Step 1: Arrange your base sticks.

Place four popsicle sticks on a flat surface, parallel and evenly spaced. In your guide, these are shown with the orange side up and the blue side down to help visualize orientation.

Step 2: Lift the base.

Gently lift the parallel sticks slightly off the surface. This begins creating the arch shape and allows weaving to start smoothly.

Step 3: Insert two cross sticks.

Weave two black popsicle sticks from the right side through the lifted structure. These sticks secure the base together and form the first layer of crossing.

Step 4: Lift again.

Carefully lift the structure higher to create space and tension for the next set of sticks. This helps stabilize the early framework.

Step 5: Add two more parallel sticks.

Place two additional popsicle sticks on top, parallel to the original base sticks, with the same orange side up and blue side down. This starts creating the layered arch.

Step 6: Weave in two more cross sticks.

From the right side again, insert two more black sticks, weaving them through the new parallel sticks. By this point, the structure should start to hold itself — this is the self-supporting stage.

Repeat and extend.

Repeat Steps 5 and 6 as often as you want to extend the bridge. Each additional layer makes it longer and stronger.

Test and fine-tune.

Once your bridge stands on its own, carefully test it by placing small objects on top. Watch how the forces distribute and adjust if needed. Try different lengths or angles to explore how the design changes.

Tips:

- Use smooth, sturdy sticks for better stability and easier weaving.

- Move slowly and gently when lifting or weaving to avoid collapse.

- Challenge yourself using pencils, chopsticks, or dowels for a different style!

Download our free step-by-step illustrated PDF guide to build your Da Vinci bridge at home or in class!

Scouts Program Worksheets and Lesson Plans for Bridge Building

Scout programs bring the construction of the Da Vinci Bridge into STEM classes. These activities connect historical engineering with what kids learn today.

Lesson plans provide background on Leonardo’s Golden Horn bridge idea. Students then investigate how the design might have worked with the technology and materials of the 1500s.

Program components:

- Historical context lessons

- Hands-on building activities

- Engineering principle discussions

- Real-world applications

Worksheets walk students through building the bridge step by step. They sneak in physics concepts along the way.

These programs show how art and engineering blend in Leonardo’s work. It’s honestly a pretty clever way to make old ideas feel fresh.

Museum Exhibits and Educational Demos: Experiencing Renaissance Engineering

Museums worldwide have set up interactive da Vinci bridge exhibits so visitors can try building real models and see for themselves how Leonardo’s ideas actually hold up.

Some museums use big models made from laminated wood or steel-reinforced timber. People even get to walk across bridges built using da Vinci’s principles—how cool is that?

Educational demos show how the Ås, Norway, pedestrian bridge made Leonardo’s vision real. The Vebjørn Sand Leonardo Bridge Project turned the old Golden Horn design into something you can experience today.

DIY da Vinci Bridge Models: From Classroom to Kitchen Table

Anyone at home can build da Vinci bridges with simple materials and a few basic tools. You only need wooden sticks and patience to figure out the interlocking trick.

Building at the kitchen table turns bridge engineering into a family project. These self-supporting models make it easy to see how sustainable design inspired modern architecture.

Using thicker sticks gives you a sturdier bridge that can withstand more building sessions. Most folks start with small bridges before trying out longer spans using da Vinci’s compression-only ideas.

Frequently Asked Questions

Leonardo da Vinci’s bridge designs are still blowing minds today. His self-supporting bridge and Golden Horn proposal show a deep understanding of structural forces and how to make things strong and beautiful.

What is special about the Da Vinci Bridge?

The Da Vinci bridge stands out for its self-supporting design—no nails, glue, or rope are needed. Thanks to compression forces and careful geometry, it stays up.

Leonardo’s Golden Horn bridge would have been 919 feet long, ten times longer than other bridges of the time.

The design used a single flattened arch so ships could pass below. Leonardo added splayed abutments for stability against earthquakes and sideways movement.

Did Leonardo da Vinci build a bridge?

Leonardo never actually built his famous bridge designs. In 1502, he proposed the Golden Horn bridge to Sultan Bayezid II of the Ottoman Empire.

The Sultan turned down Leonardo’s complicated plans, so the bridge was never built. MIT engineers later constructed a scale model that proved the design would have worked.

His self-supporting bridge stayed on paper during his lifetime. The idea only existed in his sketches and notes.

What bridge took 14 years to build?

No specific bridge is mentioned in the search results as taking 14 years to build. The first bridge across the Golden Horn—where Leonardo wanted to build it—didn’t go up until 1845.

That bridge lasted about 18 years before being replaced. Today, the Galata Bridge is the main crossing for cars and people.

Is Da Vinci’s bridge design still used today?

In 2001, Norway built a pedestrian bridge inspired by Leonardo’s 1502 design. Modern builders used steel and wood instead of stone.

Da Vinci’s self-supporting bridge is still handy for quick, temporary structures. The basic ideas continue to appear in engineering classes and workshops.

Full-scale stone versions aren’t practical now. Lighter, stronger materials have made old-school masonry bridges outdated for most uses.

What is the theory of the Davinci Bridge?

Leonardo dreamed up the self-supporting bridge in the late 1400s for military needs. The whole idea works because wooden beams push against each other in a specific geometric pattern.

Each piece locks into place based on how you position it and spread the weight. The last keystone piece holds everything together using nothing but compression.

MIT researchers figured out that shape matters most for stability. Leonardo’s work shows that engineering and art aren’t separate—they feed off each other.

What is the oldest covered bridge in the United States?

The search results don’t say much about the oldest covered bridge in the United States. It’s a bit of a tangent, since the primary focus here is Leonardo da Vinci’s bridge designs and engineering approach.

Everything available digs into Leonardo’s bridge ideas and how researchers have tried them out in modern times.

Leonardo Bianchi is the founder of Leonardo da Vinci Inventions & Experiences, a travel and research guide exploring where to experience Leonardo’s art, engineering, and legacy across Italy and Paris.

Leonardo Bianchi is the founder of Leonardo da Vinci Inventions & Experiences, a travel and research guide exploring where to experience Leonardo’s art, engineering, and legacy across Italy and Paris.